Common Chimpanzee

| Common Chimpanzee[1] | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Pan |

| Species: | P. troglodytes |

| Binomial name | |

| Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach, 1775) |

|

|

|

| distribution of Common Chimpanzee. 1. Pan troglodytes verus. 2. P. t. vellerosus. 3. P. t. troglodytes. 4. P. t. schweinfurthii. | |

The Common Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes), also known as the Robust Chimpanzee, is a great ape. The name troglodytes, Greek for 'cave-dweller', was coined by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach in his Handbuch der Naturgeschichte (Handbook of Natural History) published in 1779. Colloquially, it is often called the chimpanzee (or simply 'chimp'), though technically this term refers to both species in the genus Pan: the Common Chimpanzee and the closely-related Bonobo, formerly called the Pygmy Chimpanzee. Evidence from fossils and DNA sequencing show that both species of Chimpanzees are the sister group to the modern human lineage. The Common Chimpanzee is an endangered species.

Contents |

Study

Jane Goodall undertook the first long-term field study of the Common Chimpanzee, begun in Tanzania at Gombe Stream National Park in 1960. Other long-term study sites begun in 1960 include A. Kortlandt in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo and Junichiro Itani in Mahale Mountains National Park in Tanzania.[3] Current understanding of the species' typical behaviors and social organization are formed largely from Goodall's ongoing 50-year Gombe research study.[4]

Taxonomy

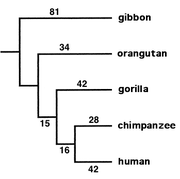

DNA evidence published in 2005 suggests the Bonobo and Common Chimpanzee species separated from each other less than one million years ago (similar in relation between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals).[5][6] The chimpanzee line split from the last common ancestor of the human line approximately six million years ago. Because no species other than Homo sapiens has survived from the human line of that branching, both chimpanzee species are the closest living relatives of humans. The chimpanzee's genus, Pan, diverged from the Gorilla's genus about seven million years ago.

Subspecies

Several subspecies of the Common Chimpanzee have been recognized:

- Central Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes, in Cameroon, the Central African Republic, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo;

- Western Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus, in Guinea, Mali, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, and Nigeria;

- Nigeria-Cameroon Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes vellerosus, in Nigeria and Cameroon;

- Eastern Chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii, in the Central African Republic, the Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Tanzania, and Zambia.

Genome Project

Human and Common Chimpanzee DNA are very similar. After the completion of the Human genome project, a Common Chimpanzee Genome Project was initiated. In December 2003, a preliminary analysis of 7600 genes shared between the two genomes confirmed that certain genes, such as the forkhead-box P2 transcription factor which is involved in speech development, have undergone rapid evolution in the human lineage. A draft version of the chimpanzee genome was published on September 1, 2005, in an article produced by the Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium.[8] The DNA sequence differences between humans and chimpanzees is about thirty-five million single-nucleotide changes, five million insertion/deletion events, and various chromosomal rearrangements. Typical human and chimp protein homologs differ in only an average of two amino acids. About 30% of all human proteins are identical in sequence to the corresponding chimp protein. Duplications of small parts of chromosomes have been the major source of differences between human and chimp genetic material; about 2.7% of the corresponding modern genomes represent differences, produced by gene duplications or deletions, during the approximately four to six million years since humans and chimps diverged from their common evolutionary ancestor. Results from human and chimp genome analyses, currently being conducted by geneticists including David Reich, should help in understanding the genetic basis of some human diseases.

Description

Adults in the wild weigh between 40 and 65 kg (88 and 140 lb); males can measure up to 1.6 m (5 ft 3 in) and females to 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in). Its body is covered by a coarse black hair, except for the face, fingers, toes, palms of the hands and soles of the feet. Both its thumbs and its big toes are opposable, allowing a precision grip. Its gestation period is eight months. Infants are weaned when they are about three years old, but usually maintain a close relationship with their mother for several more years; they reach puberty at the age of eight to ten, and their lifespan in captivity is about fifty years.

Ecology

Common Chimpanzees are found in the tropical forests and wet savannas of Western and Central Africa. They once inhabited most of this region, but their habitat has been dramatically reduced in recent years.[9]

Diet

The chimpanzee diet is primarily vegetarian, although the chimpanzee is omnivorous and also eats meat.[10] The primary chimpanzee diet consists of fruits, leaves, nuts, seeds, tubers, and other miscellaneous vegetation. Termites are also eaten regularly in some populations.[11] Western Red Colobus Monkeys (Piliocolobus badius) are sometimes hunted by the chimpanzee, although Jane Goodall documented many occasions within Gombe Stream National Park of chimpanzees and Western Red Colobus Monkeys ignoring each other within close proximity.[12][13] Chimpanzees will typically spend six to eight hours a day eating.[9]

In some cases, chimpanzees have been documented killing Leopard cubs,[14] though this primarily seems to be a protective effort, since the Leopard is the main natural predator of the Common Chimpanzee. Isolated cases of cannibalism have also been documented.

The West African Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes verus) is the only animal besides humans known to routinely create and use specialized tools specifically for hunting. Chimpanzees near Kédougou, Senegal were observed to create spears by breaking off tree limbs, stripping them of their bark, and sharpening one end with their teeth. They then used these weapons to kill galagos sleeping in hollows.[15]

Behavior

Common Chimpanzees live in communities that typically range from 20 to more than 150 members, but spend most of their time travelling in small, temporary groups consisting of a few individuals, "which may consist of any combination of age and sex classes."[10] Both males and females will sometimes travel alone.[10] Common Chimpanzees are both arboreal and terrestrial, spending equal time in the trees and on the ground. Their habitual gait is quadrupedal, using the soles of their feet and resting on their knuckles, but they can walk upright for short distances. Common Chimpanzees are 'knuckle walkers', like gorillas, in contrast to the quadrupedal locomotion of orangutans and bonobos, 'palm walkers' who use the outside edge of their palms.

The Common Chimpanzee lives in a fission-fusion society, where mating is promiscuous, and may be found in groups of the following types: all-male, adult females and offspring, consisting of both sexes, one female and her offspring, or a single individual. Chimpanzees have complex social relationships and spend a large amount of time grooming each other.[9] At the core of social structures are males, who roam around, protect group members, and search for food. Among males, there is generally a dominance hierarchy. However, this unusual fission-fusion social structure, "in which portions of the parent group may on a regular basis separate from and then rejoin the rest,"[16] is highly variable in terms of which particular individual chimpanzees congregate at a given time. This is mainly due to chimpanzees having a high level of individual autonomy within their fission-fusion social groups. Also, communities have large ranges that overlap with those of other groups.

As a result, individual chimpanzees often forage for food alone, or in smaller groups (as opposed to the much larger "parent" group, which encompasses all the chimpanzees who regularly come into contact and congregate into parties in a particular area.) As stated, these smaller groups also emerge in a variety of types, for a variety of purposes. For example, an all-male troop may be organized in order to hunt for meat, while a group consisting of one mature male and one mature female may occur for the purposes of copulation. An individual may encounter certain individuals quite frequently, but have run-ins with others almost never or only in large-scale gatherings. Due to the varying frequency at which chimpanzees associate, the structure of their societies is highly complicated.

The chimpanzee makes a night nest in a tree in a new location every night, with every chimpanzee in a separate nest other than infants or small chimpanzees, who sleep with their mothers.[10]

Chimpanzees have been described as highly territorial and are known to kill other chimps,[17] although Margaret Power wrote in her 1991 book The Egalitarians that the field studies from which the aggressive data came, Gombe and Mahale, use artificial feeding systems that increased aggression in the chimpanzee populations studied and therefore might not reflect innate characteristics of the species as a whole.[4] In the years following her artificial feeding conditions at Gombe, Jane Goodall described groups of male chimps patrolling the borders of their territory brutally attacking chimps who had split off from the Gombe group. A study published in 2010 found that chimpanzees conduct wars over land, not mates.[18] Patrol parties from smaller groups are more likely to avoid contact with their neighbors. Patrol parties from large groups will even take over a smaller group's territory, gaining access to more resources, food, and females.

When confronted by a predator, chimpanzees will react with loud screams and use any object they can against the threat. As noted above, the leopard is the chimp's main natural predator, but they have fallen prey to lions as well at the Mahale field study site, where as many as 6% of the chimpanzees studied have fallen prey to lions.[19]

Tool use

While it has been known since Jane Goodall's 1960s discovery that modern chimpanzees use tools, research published in 2007 indicates that chimpanzee stone tool use dates to at least 4,300 years ago.[20] A Common Chimpanzee from the Kasakela chimpanzee community was the first non-human animal observed making a tool, by modifying a twig to use as an instrument for extracting termites from their mound.[21][22][23] Chimpanzees have also been observed using leaves as napkins and towels.[9]

A recent study revealed the use of such advanced tools as spears, which West African Chimpanzees in Senegal sharpen with their teeth, being used to spear Senegal Bushbabies out of small holes in trees.[24] An Eastern Chimpanzee has been observed using a modified branch as a tool to capture a squirrel.[25]

Interaction with humans

Attacks

Common Chimpanzees have been known to attack humans on occasion.[26][27] There have been many attacks in Uganda by chimpanzees against human children; the results are sometimes fatal for the children. Some of these attacks are presumed to be due to chimpanzees being intoxicated (from alcohol obtained from rural brewing operations) and mistaking human children[28] for the Western Red Colobus, one of their favourite meals.[29] The dangers of careless human interactions with chimpanzees are only aggravated by the fact that many chimpanzees perceive humans as potential rivals.[30] With up to twice the upper body strength of a human, an angered chimpanzee could easily overpower and potentially kill a fully grown man, as shown by the attack on and near death of former NASCAR driver St. James Davis.[31][32] Another example of chimpanzee to human aggression occurred February 2009 in Stamford, Connecticut, when a 200-pound (91 kg), 14-year-old pet chimp named Travis attacked his owner's friend, who lost her hands, eyelids, nose and part of her upper jaw/sinus area from the attack.[33][34] There are at least 6 documented cases of chimpanzees snatching and eating human babies.[35]

Link with Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1

Two types of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the more virulent and easily transmitted, and is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world; HIV-2 is largely confined to west Africa.[36] Both types originated in west and central Africa, jumping from primates to humans. HIV-1 has evolved from a Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIVcpz) found in the Common Chimpanzee subspecies, Pan troglodytes troglodytes, native to southern Cameroon.[37][38] Kinshasa, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, has the greatest genetic diversity of HIV-1 so far discovered, suggesting that the virus has been there longer than anywhere else. HIV-2 crossed species from a different strain of SIV, found in the Sooty Mangabey, monkeys in Guinea-Bissau.[36]

Conservation

See also

- Chimp Haven

- Great Ape personhood

- Jane Goodall Institute

- List of non-human apes - list of notable individuals

- Theory of mind

References

- ↑ Groves, C. (2005). Wilson, D. E., & Reeder, D. M, eds. ed. Mammal Species of the World (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 183. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100797.

- ↑ Oates, J.F., Tutin, C.E.G., Humle, T., Wilson, M.L., Baillie, J.E.M., Balmforth, Z., Blom, A., Boesch, C., Cox, D., Davenport, T., Dunn, A., Dupain, J., Duvall, C., Ellis, C.M., Farmer, K.H., Gatti, S., Greengrass, E., Hart, J., Herbinger, I., Hicks, C., Hunt, K.D., Kamenya, S., Maisels, F., Mitani, J.C., Moore, J., Morgan, B.J., Morgan, D.B., Nakamura, M., Nixon, S., Plumptre, A.J., Reynolds, V., Stokes, E.J. & Walsh, P.D. (2008). Pan troglodytes. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 4 January 2009. Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered

- ↑ Cohen, Joel E. (Winter 1993). "Going Bananas". American Scholar.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Margaret Power (December 1993). "Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees". American Anthropologist 95 (4): 1010-11.

- ↑ Won YJ, Hey J (February 2005). "Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees". Mol. Biol. Evol. 2264553998=297–307%54565 (2): 297. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi017. PMID 15483319.

- ↑ Fischer A, Wiebe V, Pääbo S, Przeworski M (May 2004). "Evidence for a complex demographic history of chimpanzees". Mol. Biol. Evol. 21 (5): 799–808. doi:10.1093/molbev/msh083. PMID 14963091.

- ↑ Goldman D, Giri PR, O'Brien SJ (May 1987). "A molecular phylogeny of the hominoid primates as indicated by two-dimensional protein electrophoresis". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84 (10): 3307–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.84.10.3307. PMID 3106965. PMC 304858. http://www.pnas.org/content/84/10/3307.full.pdf+html.

- ↑ Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium (September 2005). "Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome". Nature 437 (7055): 69–87. doi:10.1038/nature04072. PMID 16136131. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v437/n7055/full/nature04072.html.

Cheng Z, Ventura M, She X, et al. (September 2005). "A genome-wide comparison of recent chimpanzee and human segmental duplications". Nature 437 (7055): 88–93. doi:10.1038/nature04000. PMID 16136132. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v437/n7055/full/nature04000.html. - ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "The Chimpanzees of Tanzania". Wild Kingdom. December 31, 1976.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (1968). "The Behaviour of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs (Rutgers University) 1 (3): 167.

- ↑ Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (1968). "The Behaviour of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs (Rutgers University) 1 (3): 186-8.

- ↑ "Chimps on the hunt". BBC Wildlife Finder. 1990-10-24. http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/species/Common_Chimpanzee#p004hd8g. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ↑ Van Lawick-Goodall, Jane (1968). "The Behaviour of Free-Living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve". Animal Behaviour Monographs (Rutgers University) 1 (3): 191.

- ↑ "Aggression toward Large Carnivores by Wild Chimpanzees of Mahale Mountains National Park, Tanzania". Content.karger.com. 2008-09-11. http://content.karger.com/ProdukteDB/produkte.asp?Aktion=ShowPDF&ArtikelNr=000156259&Ausgabe=238792&ProduktNr=223842&filename=000156259.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Pruetz JD, Bertolani P (March 2007). "Savanna chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, hunt with tools". Curr. Biol. 17 (5): 412–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.042. PMID 17320393. http://www.current-biology.com/content/article/fulltext?uid=PIIS0960982207008019.

- ↑ Goodall, Jane (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior.

- ↑ Walsh, Bryan (2009-02-18). "Why the Stamford Chimp Attacked". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/health/article/0,8599,1880229,00.html. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ "Killer Instincts". The Economist. 2010-06-24. http://www.economist.com/node/16422404.

- ↑ Tsukahara T (10 September 1992). "Lions eat chimpanzees: The first evidence of predation by lions on wild chimpanzees". American Journal of Primatology 29 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1002/ajp.1350290102.

- ↑ Mercader J, Barton H, Gillespie J, et al. (February 2007). "4,300-year-old chimpanzee sites and the origins of percussive stone technology". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (9): 3043–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0607909104. PMID 17360606. PMC 1805589. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/104/9/3043.

- ↑ Goodall, J. (1986). The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. pp. 535–539. ISBN 0-674-11649-6.

- ↑ Goodall, J. (1971). In the Shadow of Man. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 35–37. ISBN 0-395-33145-5.

- ↑ "Gombe Timeline". Jane Goodall Institute. http://www.janegoodall.org/jane/study-corner/chimpanzees/gombe-timeline.asp. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Fox, M. (2007-02-22). "Hunting chimps may change view of human evolution". http://news.yahoo.com/s/nm/20070222/sc_nm/chimps_hunting_dc. Retrieved 2007-02-22.

- ↑ Huffman MA, Kalunde MS (January 1993). "Tool-assisted predation on a squirrel by a female chimpanzee in the Mahale Mountains, Tanzania" (PDF). Primates 34 (1): 93–8. doi:10.1007/BF02381285. http://www.springerlink.com/content/u1g710357w253541/fulltext.pdf.

- ↑ Claire Osborn (2006-04-27). "Texas man saves friend during fatal chimp attack". The Pulse Journal. http://www.pulsejournal.com/featr/content/shared/news/stories/CHIMP_ATTACK_0427_COX.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ "Chimp attack kills cabbie and injures tourists". London: The Guardian. 2006-04-25. http://www.guardian.co.uk/international/story/0,,1760554,00.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ "'Drunk and Disorderly' Chimps Attacking Ugandan Children". 2004-02-09. http://www.primates.com/chimps/drunk-n-disorderly.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ Tara Waterman (1999). "Ebola Cote D'Ivoire Outbreaks". Stanford University. http://virus.stanford.edu/filo/eboci.html. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Chimp attack doesn’t surprise experts". MSNBC. 2005-03-05. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/7087194/. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ "Birthday party turns bloody when chimps attack". USATODAY. 2005-03-04. http://www.usatoday.com/news/nation/2005-03-04-chimp-attack_x.htm. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ Amy Argetsinger (2005-05-24). "The Animal Within". The Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/05/23/AR2005052301819.html. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- ↑ "911 tape captures chimpanzee owner's horror as 200-pound ape mauls friend". Nydailynews.com. 2009-02-18. http://www.nydailynews.com/news/2009/02/17/2009-02-17_911_tape_captures_chimpanzee_owners_horr-2.html/. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ By Stephanie Gallman CNN (2009-02-18). "Chimp attack 911 call: 'He's ripping her apart' - CNN.com". Edition.cnn.com. http://edition.cnn.com/2009/US/02/17/chimpanzee.attack/. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ "Online Extra: Frodo @ National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. 2002-05-15. http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0304/feature4/online_extra2.html. Retrieved 2009-06-06.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Reeves JD, Doms RW (June 2002). "Human immunodeficiency virus type 2". J. Gen. Virol. 83 (Pt 6): 1253–65. PMID 12029140. http://vir.sgmjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12029140.

- ↑ Keele BF, Van Heuverswyn F, Li Y, et al. (July 2006). "Chimpanzee reservoirs of pandemic and nonpandemic HIV-1". Science (journal) 313 (5786): 523–6. doi:10.1126/science.1126531. PMID 16728595.

- ↑ Gao F, Bailes E, Robertson DL, et al. (February 1999). "Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes". Nature 397 (6718): 436–41. doi:10.1038/17130. PMID 9989410.

- General references

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, De Generis Humani Varietate Nativa, 1775.

- Tutin CEG, McGrew WC, Baldwin PJ 1983. Social organization of savanna-dwelling chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, at Mt. Assirik, Senegal. Primates, 24, 154-173.

External links

- Fisher Center for Study and Conservation of Apes, Lincoln Park Zoo, Chicago

- DiscoverChimpanzees.org

- Chimpanzee Genome resources

- Primate Info Net Pan troglodytes Factsheets

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Species Profile

- New Scientist 19 May 2003 - Chimps are human, gene study implies

- Video clips and news from the BBC (BBC Wildlife Finder)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

[[Category:Mammals of Côte d'Ivoire